On a fascinating trip to Cognac, France, I was reminded of the power of innovation in the face of hardships and how commerce finds a way to survive and grow communities around it.

When you think of Cognac, you think of France. It is, after all, named after the region in France that gave it its name. What could be more French than a baguette, some brie, and a Cognac with a side of Gitanes, perhaps? Well, as it turns out, the liquid Cognac was created by the Dutch from French wine, refined by the English, then mastered by the French, and saved by… Americans.

For the last few months, tariffs and trade wars have been mentioned many times daily, emanating from the US. With this as a backdrop, it's hard to imagine a time when Thomas Volney Munson, a proud Texan (sound familiar?), was awarded the highest honor a non-French national could receive—the Chevalier du Merite Agricole—and was inducted into the Legion of Honor in 1888 for literally saving France's hugely important wine industry. Indeed, that partnership between Cognac and Denison, TX, still holds today, well over a century and a half later.

The history of Cognac is a long and well-reported one, and I urge you to have a read. Even the Grand and Petit Champagne versions of Cognac owe their names (and that of another French staple—Champagne) to… the Italians. Ever wondered how a southern French product can call its most prodigious version 'Grand Champagne Cognac' when the Champagne region is 650 km north and vociferously protected on pain of death if you call something by that name without permission?

When France was invaded by Romans, they found the area around Cognac and its chalk soils to be reminiscent of their beloved Campania region and named it so. Over time, it evolved into an area of 34,000 vine-growing hectares, and the families of the wine industry set the rules for what constitutes the very best Cognac. After the south was conquered, the Romans went north and found another region with chalk soil and hills, naming it Campagna as well—the Champagne region of today. Perhaps it was a different set of soldiers, or they simply forgot that they already had another Campania in France, as it can get confusing if they're left to naming the regions.

History is all too often forgotten or simply not known, which is a shame, as it provides a sobering dose of wisdom and a better worldview. The French have always imported vines for their fabled wine-growing from all over the world. Italy, Portugal, Greece, the USA, and more have all contributed vines to their industry. This was happening centuries ago; it's not just a new thing, and it's all based on relationships and commerce.

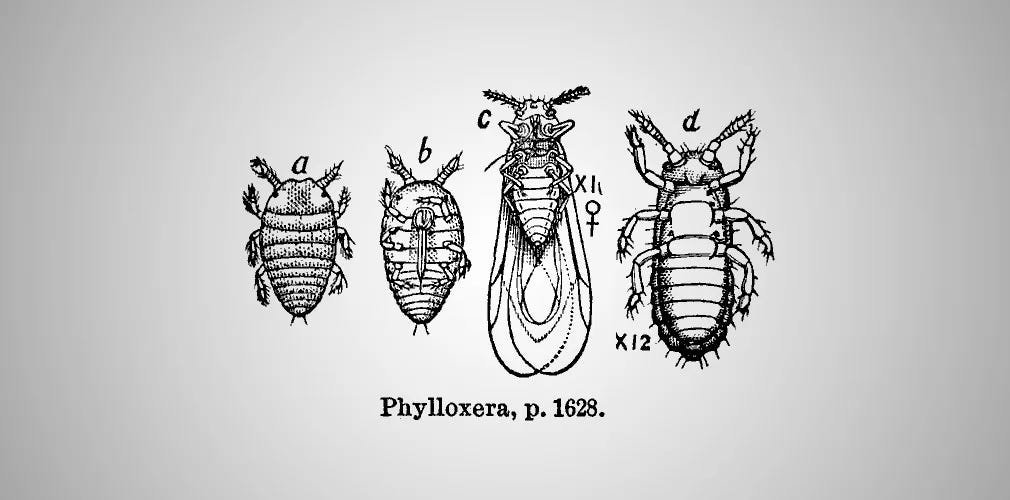

Sadly, in the 1800s, they also unknowingly imported something from the USA that destroyed their crops and neighbouring countries' crops as well. The great phylloxera root louse wasn't something anyone could have imagined, and it was a crisis. In 1863, starting in the Rhône region of France, the louse spread rapidly. In France alone, they estimate wine production fell from 84.5 million hectolitres in 1875 to only 23.4 million hectolitres in 1889. That's devastating for any industry. They think that between two-thirds and nine-tenths of all European vineyards were destroyed.

As you can imagine, there was panic. Vignerons used to chain toads to the bottom of their vines in desperation to kill the louse, along with many other drastic methods, none of which actually worked. Even today, there's no cure for infected vines. The scientists laboured long and hard to come up with an answer, and finally, there was hope.

Mr. Munson in Texas came to the rescue and provided a vine that had a louse-resistant rootstock, which the scientists had proven could be grafted to other vines. All anyone wanted to do was to get back to growing and drinking wine again. It didn't change the grapes up top; it just made them able to grow again, unaffected by their roots being eaten by the louse.

A cartoon from Punch from 1890: The phylloxera, a true gourmet, finds out the best vineyards and attaches itself to the best wines

Back to Cognac—for a long time, it was a grape called the Folle Blanche that was the primary grape variety used for making Cognac, but it was significantly impacted by the phylloxera, and even grafted stock couldn't handle the little blighters that were set loose. Facing an existential threat to their entire brand of liquid, the grand families of Cognac got together and again changed the rules—including, amongst others, the Ugni Blanc grape variety that's now the dominant grape in Cognac production. It was a robust grape that could resist the louse and could get their gravy train back on track again—and so it very much did steam ahead to today with the very same methods and traditions.

Now Cognac is facing many other threats. Recently, the Chinese, in response to the EU looking at electric vehicles being dumped from China, retaliated, saying Cognac was being 'dumped' in their markets and, amongst other measures, added an exclusion from Duty-Free channels. This has drastically hit their second-biggest market. If the US, which is absolutely their largest market, imposes a 25% tariff, the industry, already on its knees, will again be facing an existential crisis.

It takes, depending on the type of Cognac, between 19 and 15 litres of wine to make 1 litre of Cognac. The rules state that the stills have to be heated by an open flame. It has to be at least double distilled. It has to age for at least two years in oak barrels only. The costs mount up quickly on a drink that's already too pricey for most, so adding any percentage is going to reduce the opportunity for purchase to even fewer people.

The history of Cognac is a story of adaptation. As with many other stories, they were dealt a shitty hand, but together as a global community, they managed to get livelihoods back on track. Today, there's an entire ecosystem based around the region, providing barrels, knowledge, skill, grapes, transport, tourism, and everything needed to keep the trade as a provider for livelihoods. They faced down one threat through innovation, and perhaps through dialogue, they hope to face down another one.

While tariffs and trade wars pose significant challenges, they also present opportunities for those who can adapt and find new markets. The Cognac industry may be facing an uncertain future, but its history suggests that it has the tenacity and ingenuity to weather the storm.

As investors, we can learn from Cognac's resilience, and possibly their way of making new rules that help to level the playing field a bit more. In times of adversity, innovation and collaboration can pave the way for survival and growth.

Partnering with HindeSight can allow everyone a shot at rewriting the rules of a traditional Investor and allowing them insights not usually provided to everyone. We were set up to democratise investing and hope you’re along for the journey. At soe stage we might even share a Cognac.

Happy Investing!